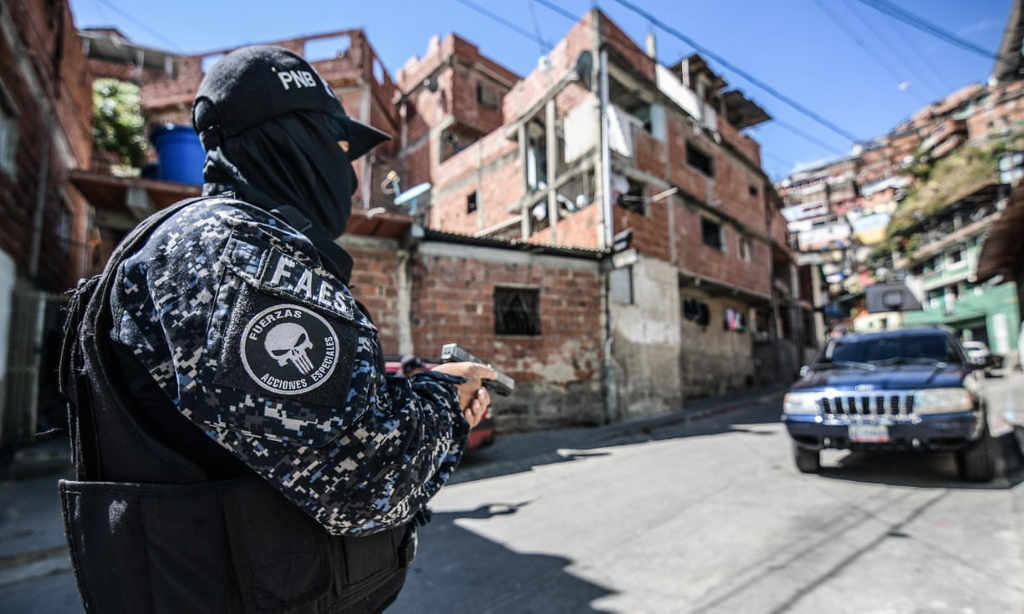

Nicolás Maduro’s special forces set up camp on Petare’s doorstep just days after efforts to depose him began, daubing the pitch black exterior of their base with their commander-in-chief’s call to arms: “Always loyal, never traitors”.

Alongside, troops painted two white skulls and a second chilling mantra: “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.”

Almost three months later, black-clad operatives stare down from the compound’s wooden rampart, assault rifles trained on slum-dwellers once considered Chavismo’s most fervent supporters.

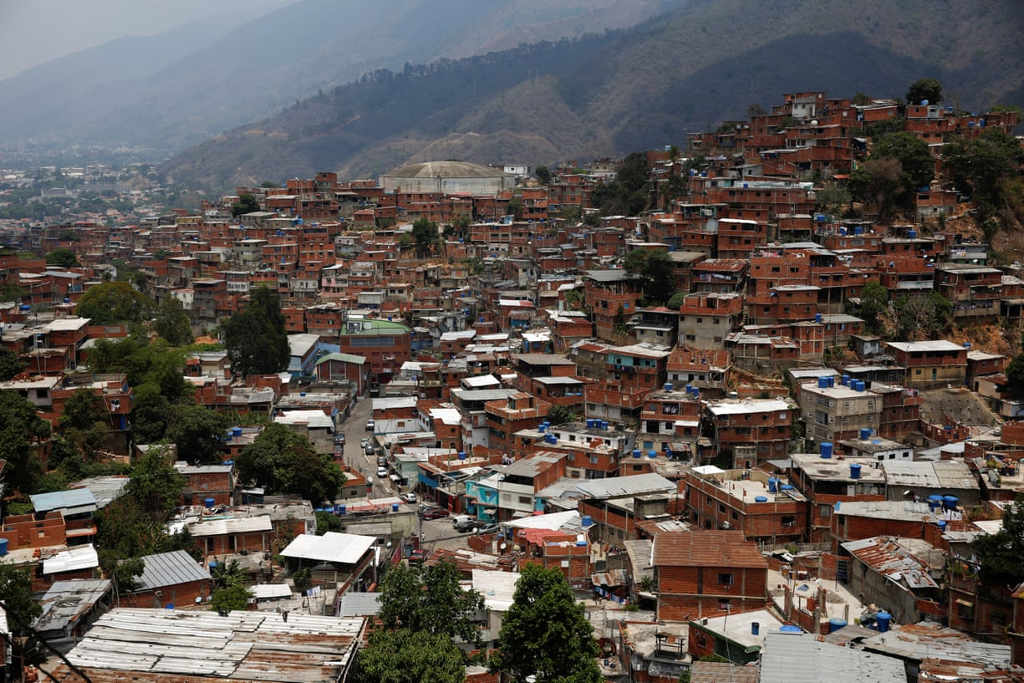

“It’s a way of intimidating the population,” complained José Luis Castañeda, a community leader in this vast tapestry of redbrick homes in eastern Caracas. “But it won’t sway the petareños.”

Seventeen years earlier, Castañeda was one of tens of thousands of people who streamed down from their hilltop homes to defend Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, when he was briefly deposed by a botched US-backed coup.

For millions of disenfranchised citizens, Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution represented, finally, the possibility of social, economic and racial inclusion in a profoundly lopsided society.

But now, with their lives upended by the economic and social disaster unleashed under Maduro, many of those same marchers are turning on Chávez’s successor in what could prove a fatal blow to his rule.

“Maduro is a delinquent. Maduro is wicked. Maduro is a monster. He is evil … The people no longer want him,” fumed Magaly Arismendi, a 54-year-old manicurist from El Campito, one of dozens of working class communities that make up Petare.

Across Petare’s vertiginous back alleys such anger is inescapable – even if some still lionize Chávez as a champion of the poor.

“Petare was Chavista. Not any more,” said Héctor Lunar, a Catholic priest who lives and works in the community and is part of the opposition movement to dethrone Maduro. “Most here are against the government and they are crying out for change.”

A man of the cloth, Lunar is more diplomatic than most.

Joel Rivero, another community leader, said the rage was such that Maduro would be lynched if he showed his face in Petare. “And I’ll tell you something: I’m a practicing Catholic … but I think I’d take a piece of him myself … because there’s no name for what they have done to Venezuela.”

Franklin Piccone, a local teacher and activist, said many felt so desperate they hoped a missile would obliterate the presidential palace, Miraflores, and its occupants.

“People don’t care any more – they just want these people out,” Piccone said. “If you ask me, [they must go] if they don’t want to end up like Gaddafi … We really are now facing a social explosion.”

But as Venezuela’s political mutiny enters its third month, that often untamed rejection of Maduro has yet to translate into universal support for his challenger, Juan Guaidó.

Alexis Pineda, an 18-year-old student from El Campito, said that for all his community’s hardships he felt ambivalent about both men.

“The way I see things, neither of them has done anything,” he grumbled. “All right, Guaidó declared himself president … but we haven’t heard much from him since.”

Advertisement

José Jaramillo, a 32-year-old construction worker, said the political crisis had left him feeling like an orphaned child: “None of them are any good. Not Maduro. Not the opposition. None of them.”

William Pirela, a 45-year-old window fitter, said he was optimistic Guaidó could drag Venezuela out of a crisis that had forced his two daughters to flee to neighboring Colombia in search of work.

But Pirela admitted he was too scared to take to the streets on behalf of Maduro’s challenger, having seen a friend killed during a previous round of anti-government protests.

“They are nice and safe in their homes … They are protected by bodyguards and police and the rest of it,” Pirela said of the opposition’s leaders. “What about us?”

Venezuela’s impoverished barrios have been making their voices heard in the weeks since Guaidó threw down the gauntlet to Maduro on 23 January – and have paid dearly for it, with human rights activists accusing security forces of a string of politically driven killings.

But opposition leaders and activists say the unequivocal backing of the barrios is essential if Guaidó is to prevail over Maduro – hence Maduro’s use of special forces and paramilitary gangs known as colectivos to snuff out even the slightest hint of rebellion.

“If the people who live in the barrios rise up and say, ‘No more!’ that will be the end of Maduro,” predicted Henrique Capriles, a prominent opposition leader who narrowly lost the 2013 presidential election to Maduro and is now backing Guaidó.

Advertisement

Capriles said he did not believe Venezuelan soldiers – many of whom themselves hail from the slums – would open fire if barrio residents mobilized en masse, meaning it was imperative for Maduro to stop things going that far.

“This is the crossroads at which Maduro now finds himself … and this is why he needs to … extinguish [any kind of uprising] immediately – with repression,” Capriles said. “The regime knows that if the barrios wake up … they will remove Maduro.”

‘We call it survival’: Venezuelans improvise solutions as blackout continues

Read more

In recent days, as Venezuela has grappled with a succession of devastating blackouts that have hit slum dwellers particularly hard, Guaidó has shown signs of understanding the need to do more to win over the hearts and minds of the barrios.

“You have the power to change this country,” he told crowds during a visit to El Valle, a working class stronghold in south-west Caracas.

Lunar, who has worked in Petare since 2012, predicted that once Guaidó had the barrios on board “many things will start to change rapidly”.

But for that to happen, “a profound reconciliation” was needed between Venezuela’s opposition – long regarded as an opulent, aloof, and overwhelmingly white elite – and the poor, “and this needs to start now”. “If we want the people to speak out, the leadership must get close to the communities,” Lunar said.

Capriles said he had advised Guaidó to travel widely outside the capital in order to create an unstoppable political “snowball” that would drive Maduro out. “Caracas is not Venezuela. You have to visit the people in Maracaibo, in San Juan de los Morros, in Ciudad Guayana – and you have to set about getting the Venezuelans to believe in the struggle, so they can overcome fear.”

As petareños wait for Guaidó to visit, the priority for most remains day-to-day survival in a country no longer able to provide a reliable supply of water or electricity to its people.

“The situation is terrible. Our children are fleeing the country,” said Rosa Cárdenas, a 68-year-old resident of Los Algarrobos, one of Petare’s most deprived sectors, who had spent the last four days without water.

Hyperinflation was so dire that it now cost her entire pension of 18,000 bolívar es to buy a single bottle of washing up liquid. “If it wasn’t for my children helping me, how would I eat?” she wondered.

As she spoke, Venezuela suffered the latest in a succession of massive nationwide blackouts and the whole of Petare was plunged into a sinister gloom.

Shouts of “Maduro, coño’e tu madre” – the opposition’s risqué rallying cry – echoed across the hilltops. “Maduro, get fucked.”

“I feel afraid. I feel anger. I feel hatred,” said Cárdenas, as her neighbors placed improvised oil lamps outside their electricity deprived homes. “The truth is, it’s all just too much.”

Cárdenas did not hesitate in declaring herself part of the opposition to Maduro but admitted she was still not completely convinced by Guaidó.

As she sat in the shadows, the grandmother of six scoffed at the chirpy slogan of his campaign to topple Maduro: “Vamos bien”, or “We’re doing well”.

“We’re well fucked, that’s what,” she said.

Source The Guardian