Centro Financiero Confinanzas, also known as Torre de David (the Tower of David), is an unfinished abandoned skyscraper in Venezuela’s capital city, Caracas, the third highest building in the country after the twin towers of Parque Central Complex.

To those unaware of its history, the Centro Financiero Confinanzas looks like any other unfinished skyscraper, located in the financial district of Caracas. At 45 stories high, it is also the eighth tallest building in Latin America.

Its glass facade glimmers in the sun, a projection of wealth and economic prowess that was intended to house national and international businesses. Inside, however, hides a rather different reality.

Construction and banking crisis

The construction of the tower began in 1990 but was halted in 1994 due to the Venezuelan banking crisis. Construction ground to a halt. It lay unoccupied and unfinished, an ironic symbol of financial failure that was intended to represent the unstoppable march of Venezuela’s petro fuelled booming economy.

The complex has six buildings: El Atrio (Lobby and conference room), Torre A that is 190 meter tall and stands at 45-stories still includes a heliport, Torre B, Edificio K, Edificio Z, and 12 floors of parking.

During the banking crisis of 1994, the government took control of the building and it has not been completed since. The building lacks elevators, installed electricity, running water, balcony railing, windows, and even walls in many places.

In 2001, the Venezuelan government made an attempt to auction off the complex, but no one made an offer.

Residence by squatters

A shell, a skeletal construction whose bare structural bones became, in October of 2007, a remarkable opportunity for an intrepid group of squatters, families whose economic and social situation led them to seek a new life in a space intended for stockbrokers and bankers, their potential interaction with the grinding poverty at ground level negated by the presence of a helipad.

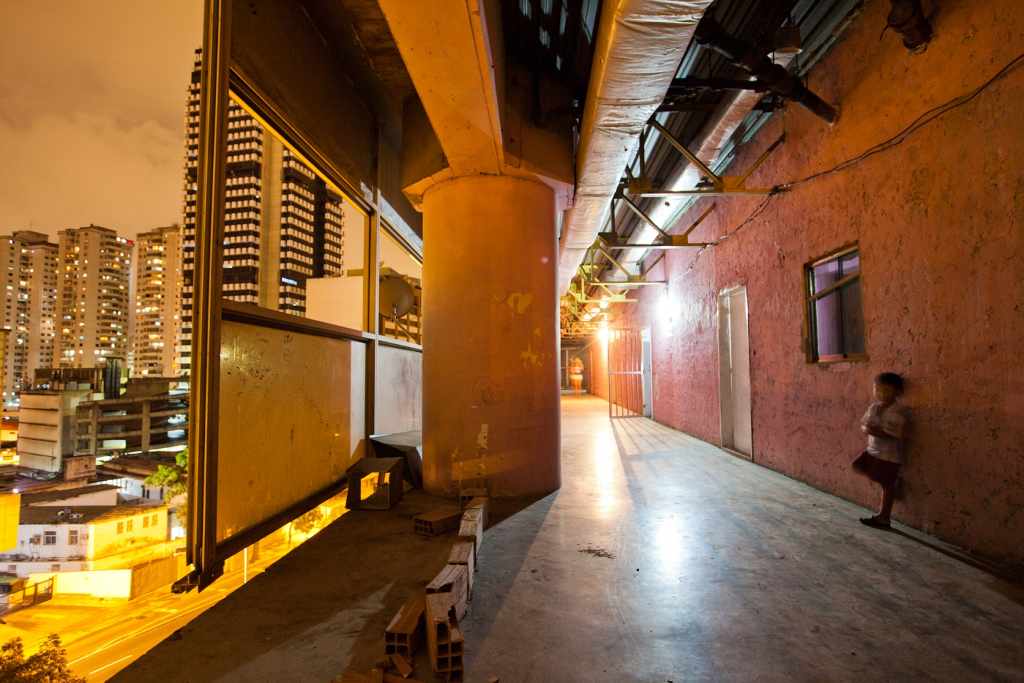

Families whose search for a decent home had led them to risk forging a new life 30 floors up, reminded constantly of their precarious position by the wind that whipped through their sparse living quarters. The views were incredible but deadly, a god like view of a city that had failed to accommodate its newest inhabitants.

They made use of cheap building materials, breeze blocks and tarpaulin, cardboard and corrugated iron, to construct their homes. It is a formula that has been endlessly repeated and replicated around the world, from the favelas of Rio de Jainero in Brazil, to the shanty towns of India, hastily arranged dwellings that initially provide temporary shelter.

See Squatters in Venezuela’s 45-Story ‘Tower of David’ photo essay from The Atlantic

The construction of homes, the imposition of a personal space in which to live, was illegal, a form of trespassing in a building that belonged to a government supposedly tasked with providing a decent living space for its citizens. Yet the difference with Torre David is that there was only one way to keep building. Up. Yet with all temporary dwellings, bits and pieces are added, living space expanded as and when the money to construct them becomes available.

Materials were precariously carried up bare concrete staircases as homes began to take shape. Basic necessities such as electricity and toilets were rigged up rudimentarily. The tower began to become more than a shell, its residents had illegally and crudely started to finish the job that had started some 17 years before, a potent emblem of a resourceful population becoming self-sufficient in the face of government ineptitude.

Because whilst the ‘Torre David’, so named after its main investor David Brillembourg, who died from cancer in 1993, may look like the newest high rise addition to the Caracas skyline, it is actually became home to over 700 families, a ‘vertical slum’ that was a truly fascinating example of reappropriation of space in an urban environment.

Residents improvised basic utility services, with water reaching all the way up to the 22nd floor. They could use motorcycles to travel up and down the first 10 floors, but had to use the stairs for the remaining levels. The residents lived up to the 28th floor. Some residents even had cars, parked inside of the building’s parking garage.

The population grew from over 200 families in October 2007, representing about 40% of Caracas’ “informal communities”, to seven hundred families made of over 2,500 residents living in the tower by 2011 and had a peak population of 5,000 squatters.

The occupation of the tower, however, was more than just a search for living space. A flourishing economy built up inside its concrete walls, hairdressers, grocery stores and workshops served the burgeoning community of increasingly settled occupants.

The towers fundamentally isolated nature – bear in mind it was originally intended as a sanctuary for the city’s gilded workforce amongst the noise and chaos of urban Caracas– have fomented a strong sense of community, utopic even. Roots were set down and the flowering buds of a society emerged, anchoring the tower with more than its massive foundations.

Yet it was not without its dangers. Stories of children playing dangerously close to the edges, falling to their death even, were a constant worry.

Relocation

On July 22, 2014, the Venezuelan government launched so-called “Operation Zamora 2014” to evacuate hundreds of families from the tower and relocate them into new homes in Cúa, south of Caracas, as part of its Great Housing Mission project.

By June 2015, all of the residents were relocated to their new homes. Some of the government-provided homes designated for relocated tower residents were already occupied by squatters who had taken over the government facilities.

Possible future

Alfredo Brillembourg, relative of the late David Brillembourg who was a main investor of the tower, founded Urban Think Tank, which call on international attention for developing “informal settlements”.

The group made a documentary on how to make potential improvements with the complex which won a Golden Lion at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale of the Venice Biennale.

After relocation had proceeded in July 2014, newspaper Tal Cual reported that Chinese banks were interested in buying the tower and renovating it for its original use. On July 23, 2014, President Nicolás Maduro announced that the government had not yet decided what to do with the building, but was considering at least three possible options: “Some are proposing its demolition. Others are proposing turning it into an economic, commercial or financial center. Some are proposing building homes there. …We’re going to open a debate.”

In April 2015, the head of the government of the Capital District, Ernesto Villegas, announced that the tower would be used temporarily as a center for emergency care. Villegas indicated that members of the National Guard, Fire Department, and officials from the Directorate of Civil Protection would be installed in the building to serve the public.

However, in April 2016, it was reported that the Chinese bank proposal fell through and that the tower was not in use. Since then, the tower has remained incomplete.

Today, in 2018, the building remains incomplete and unused. It was damaged due to two earthquakes on August 21 and 22, 2018, when a magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck just off the northern coast of Venezuela, near Cariaco, Sucre. The tower was significantly damaged by the earthquake which caused the partial collapse of the top five floors, resulting with the affected portion leaning outward by 25 degrees.

Sources:

See also