Since our last article in this series there have been significant changes in the administration of citizen security in Venezuela. The murder of actress Monica Spear and her husband last month effectively provided the occasion for the Maduro government to accentuate the militarization of the administration of citizen security, replacing civilians with military officers both at the helm of the National Experimental Security University (UNES) — where security forces receive training — and the National Bolivarian Police (PNB). This means that the entire citizen security apparatus is now directed by retired or active military officers.

What do citizens think about the armed forces in citizen security functions? In Datanalisis’ September-October tracking poll we asked respondents: Among the following options, which makes you feel the safest?

This article originally appeared on the Washington Office on Latin America blog Venezuela Politics and Human Rights. See original article here.

The results are clear and remarkable. Respondents preferred the National Guard to the police by a ratio of 4:1 (57 percent versus 14 percent). Furthermore, almost twice as many respondents preferred the presence of neither to the presence of the police (27 percent versus 14 percent). Despite the National Guard’s reputation for being heavily armed but lightly trained, and the excessive use of force this frequently leads to, people clearly prefer them over the police.

This should not be taken as an indictment of the PNB since, thus far, they have only been deployed to eight states (including the capital, Caracas) and have around 15,000 officers working in the entire country. This can be compared with the Metropolitan Police that, before being disbanded, had about 10,000 officers working in Caracas alone. Rather, this demonstrates the distrust that decades of corrupt and abusive police have generated.

Political scientist Ana Maria Sanjuan, a leading authority on citizen security and policing in Venezuela, suggests there are several factors at work. She suggests that people see career police officers as corrupt, abusive and frequently in cahoots with criminals. They fear that approaching them to report a crime would most likely lead to harassment and extortion rather than protection. In contrast, while National Guard troops are heavily armed, they are generally on brief rotations in any given sector and therefore less likely to create durable networks with criminals. And while they do not have extensive training, average people see them as more honest and less likely to harass them.

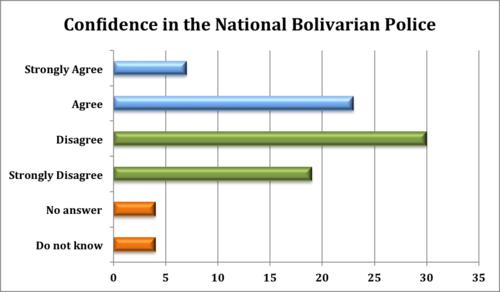

How do people see the effectiveness of the PNB? On the survey respondents were asked: Do you agree with the following statement? The National Bolivarian Police is the security body most capable of combating security.

Almost half of respondents do not perceive the PNB as the most capable police force, compared to 30 percent who do. When we break this down by political affiliation, we see a clear division between government supporters and the opposition. 56 percent of government supporters were in agreement, compared to 9 percent of opposition supporters. In contrast, 81 percent of opposition supporters disagreed with the statement compared to only 21 percent of government supporters disagreeing.

There are two possible explanations for the importance of political affiliation in this data. First, the PNB and the UNES are both identified with the Chavez and now Maduro government. Thus those who oppose the government are more likely to oppose its initiatives. Second, and more generously, the popular sectors that most support the government are also the places where the PNB have been deployed most intensively. Thus it could be that people with more contact with the PNB have a more positive view of its effectiveness.

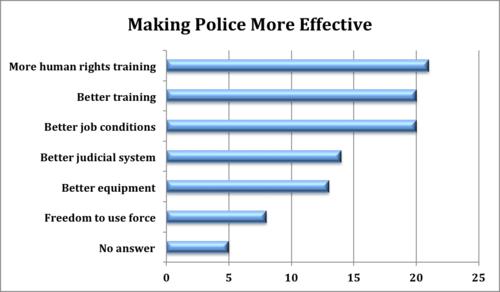

What do citizens think would make police more effective? The following question was included on the September-October survey: In your opinion, in order for our police officers to be more capable of fighting crime, what is the first thing that needs to happen? Respondents were given six options: More training in the protection of human rights, better training, better job conditions (salary and benefits), a better functioning judicial system, better equipment, and more freedom in using force when confronting criminals.

Surprisingly, the response that receives most support is the idea of receiving more human rights training, narrowly edging out “better training” and “better job conditions,” although still receiving less than a quarter of all the responses. Interestingly, here there is agreement across political lines. When broken down by affiliation, 22.9 percent of government supporters and 22.8 percent of the opposition believe that more training in human rights is the first thing that needs to happen to improve the police’s ability to fight crime.

“Freedom to use force” received less than 10 percent of responses. However it is important to realize that the question was what needs to be done to make the police more effective. Many people probably think use of force is important, but simply do not think the police need more freedom to use it.

The responses to these three survey questions provide a complex portrait. Venezuelans are still overwhelmingly dissatisfied with their police forces and trust the National Guard much more. Furthermore, the newly created PNB has not fully convinced people of their effectiveness, a perception that is affected by Venezuela’s political polarization. However, the data show broad support for better trained and better paid police forces, and most particularly for human rights training.

*This article originally appeared on the Washington Office on Latin America blog Venezuela Politics and Human Rights. See original article here.

- Venezuela

- security policy

- Police Reform

- Tools and Data