Calamar, Colombia. Out Of Options, Venezuelan exiles turn to prostitution to feed their families. Back in Venezuela, they were teachers, police officers and newspaper carriers, but were forced to flee their homeland in search of work and money to survive.

But the women, without identity papers, ended up working as prostitutes in sordid bars in Colombia, saving all they can to provide for their families back home, still in the throes of economic crisis.

Mother-of-three Patricia, 30, was beaten, raped and sodomized by a drunken client — but she keeps on working in a brothel in Calamar, in the center of the country.

“There are customers who treat you badly and that is horrible,” she says. “Every day, I pray to God that they are good (to us).”

Alegria is a teacher of history and geography but in a Venezuela gripped by chronic hyperinflation, she was earning less than a dollar. Her salary was not enough “even for a packet of pasta,” the 26-year-old mother of a four-year-old boy told news agency AFP.

In the Venezuela of hyperinflation and the economic crisis, her salary of 312,000 bolivars (less than a dollar) was no longer “enough to buy some pasta,” says the 26-year-old migrant.

In February, she crossed the border into Colombia.

She initially worked for three months as a waitress in the east, a job which offered room and board, but Alegria was never paid, getting by on tips. “What I sent to my home were tips,” she says. Six people, including her four-year-old son, were relying on her.

Eventually, even those were confiscated, so Alegria made her way south to Calamar, which is located in an area scarred by decades of armed civil conflict. The region is a hub for drug-trafficking, and a bastion of dissident former FARC guerrillas.

With nine other women, Alegria — a nickname that in Spanish means ‘happiness’ she chose with irony — prostitutes herself every night in one of the bars in the tolerance zone of this dusty town of 3,000 inhabitants. Some 60 other Venezuelan women do the same work here.

Customers (johns) pay between 37,000-50,000 pesos (US$11-16 dollars), of which 7,000 is kept by the bar. On a “good night,” Alegria can earn the equivalent of between US$30 and US$100.

“It never crossed our mind to prostitute ourselves. We did it based on the crisis,” says Joli — another nickname — 35, with a choked voice. In 2016 she lost her job as a newspaper distributor in Venezuela. “There was no more paper to print them!”

Trusting her three children to her mother, she went from city to city, from one job to another. Without a passport, Joli crossed the border without a suitcase, only with the clothes she was wearing.

Joli explains she lost the man she was going to marry, the father of her children, “from renal failure, due to lack of medication”.

“Because of the crisis”

After four years of recession and years of financial mismanagement, Venezuela’s crisis has seen poverty soar as basic necessities such as food and medicine became scarce.

Inflation is set to hit a staggering 1.4 million percent this year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which says 2019 will see that figure reach an astronomical 10 million percent.

Some 1.9 million Venezuelans have fled the crisis-ridden country since 2015, according to the United Nations (UN).

Out of options

Women like Joli, whose backs are against the wall, can’t even find work as a cleaner because of their Venezuelan accent.

In Bucaramanga (northeast), 575 kilometers from Calamar, “I saw myself between a rock and a hard place,” she says. “Because of my tone of voice, they closed the door in my face.”

After having doors closed in her face she ended up in Calamar, she opted to “sell” herself, turned to sex work. In June, her 19-year-old niece, Milagro, joined her at the brothel.

“At first I felt super bad,” says Milagro. But she persisted in the absence of a better alternative to help her brothers, her two-year-old baby and her sick mother, who later died.

Beside the financial hardships and obvious unpleasantness of the work, many women struggle with hiding the truth from their families.

“They don’t know what I do, even my mother,” admits Alegria. “It would be too difficult for her after sacrificing five years of her life to pay for my studies.”

She dreams of beaing a teacher in Colombia but without a passport, it’s impossible. So, she tells her family she works in a bakery but, is sick of lying.

Anxiety, depression, PTSD

Jhon Jaimes, an MDM psychologist, says the women suffer from “anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder.” Their fear of the armed men in the region is very real. On top of that, the tropical climate exposes them to infections such as dengue and malaria.

Then there are sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancies that result when clients refuse to wear condoms.

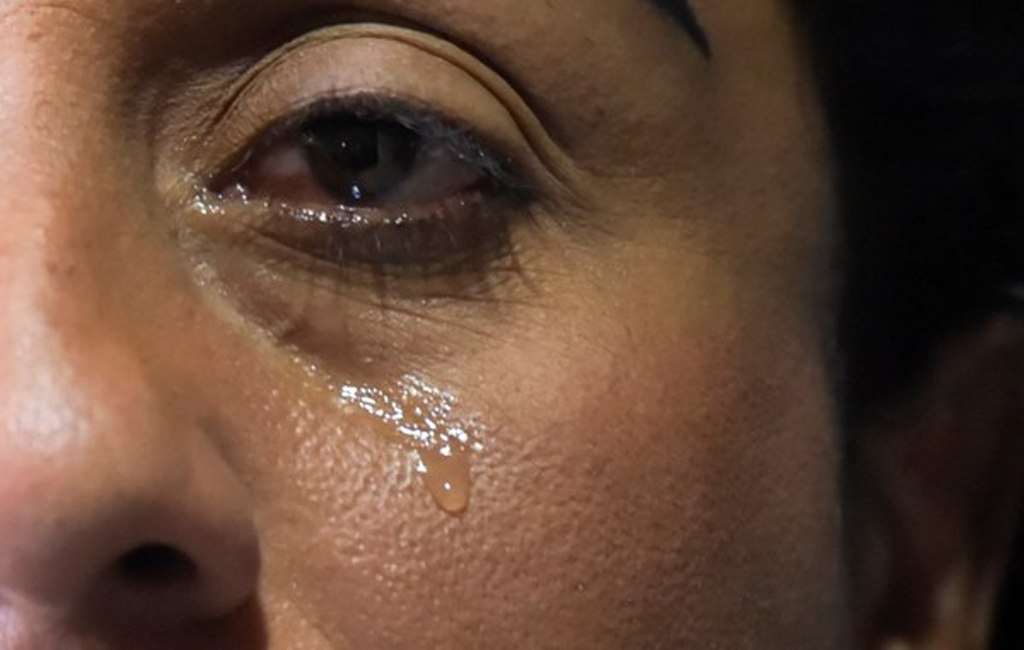

At the Doctors of the World (MDM) hospital in Calamar, a doctor treats them, fits them with birth control implants and offers advice. MDM gives them food, hygiene products and contraceptives. Some break down in tears.

It’s an unforgiving life, but one not entirely without hope.

Escape

Former police officer Pamela, 20, went to San Jose del Guaviare, a three-hour drive from Calamar, for an abortion and managed to continue on to the greater Bogota area.

She now works as a waitress for US$10 a day — only 10 percent of what she could make in the brothel, but one she prefers over in Calamar, where she was basically her pimp’s property.

“This guy lied to us,” she says ruefully.

Milagro has also found a way out, in the form of a pilot she is now dating. Mother-of-four Alejandra, 37, says she isn’t looking for a husband. “One man isn’t enough. I need a lot to feed the little ones,” she says.

Her youngest child, just two months old, was fathered by a client.