The UN’s latest homicide report paints a bleak picture of the security situation in the Americas, where some battered governments face epidemic levels of violence, although selected success stories provide hope for improvement.

Largely based on homicide figures from 2012, the United Nations 2013 Global Study on Homicide (pdf) builds on its first homicides report issued two years ago (pdf), updating statistics based on new datasets, and delving deeper into the drivers of intentional killings as well as prevention policies.

For the Americas, beyond the revelation it has now superseded Africa as the world’s most violent region, there were few surprises, with the report reinforcing the common image of a region racked by organized crime-driven violence further complicated by high levels of impunity. Perspectives on the role of organized crime are particularly relevant to Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the effectiveness and capacity of the criminal justice system and the efficacy of schemes based around social inclusion in addressing violence.

According to the report, of the world’s 437,000 homicides in 2012, more than a third (36 percent) took place in the Americas — a region encompassing North America, Latin America and the Caribbean. The distribution of murders in the region also reveals an even greater concentration, with Honduras remaining the most violent country in the world (with 91.4 homicides per 100,000 people) along with high rates in El Salvador, Guatemala and Belize, making Central America’s “Northern Triangle” the world’s second most violent sub-region behind Southern Africa.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Homicides

The Role of Organized Crime

One of the most prominent messages in the report is the central part played in Latin American murders by organized crime and gang-related activity, which accounts for 30 percent of all killings in the region (up from 25 percent reported in the 2011 study). This compares to less than one percent in Asia, Europe and Oceania (down from five percent reported in 2011). Yet while such criminal groups catalyze murders in Latin America, the report points out that this does not necessarily mean the organized crime presence is more concentrated than elsewhere, rather that there is a predisposition to violence, in part related to struggles among criminal groups or with local authorities.

As the report states, “Such groups in the Americas may be experiencing higher levels of conflict with each other, or with the State, than organized criminal groups in other regions, which, though they may also be active, may have reached a level of stability or control over their territory and resources that does not generate the same level of visible violence.”

In Latin America patterns of criminal fragmentation, diversification and migration combine to produce extreme violence. Not only do criminal organizations engage in bloody wars against rivals — such as those waged in recent years in Colombia by the Urabeños — but organizations themselves are engulfed in internecine conflicts as competing factions attempt to establish control over criminal empires. Such conflict and fragmentation can be exacerbated by government tactics, with Mexico’s cartel decapitation policy a key factor in the chaos and bloodletting seen within criminal organizations in recent years.

Understanding this dynamic is complicated further by the fact that in some extremely violent countries drug trafficking organizations work relatively peacefully, such as in El Salvador and Guatemala, where traditional “transportista” groups maintain close relationships with officials at the highest level and have conducted their illegal activities with impunity for many years. In these countries, it is street gangs that drive violence, with that reality highlighted in El Salvador when the homicide rate halved in 2012 following the implementation of a truce between the country’s two main gangs.

Impunity and Police Corruption

Linked to the prevalence of organized crime-related killings is the abysmal conviction rate for murder cases, with just 24 percent of reported homicides in the region resulting in a conviction — little more than half the global average of 43 percent and less than a third of the 81 percent conviction rate enjoyed in Europe (click on UN graph to open in new window).

The reasons for this are many, with the lower clearance rate associated with organized crime-related killings a key factor, as well as stretched police resources and corruption.

While police corruption is a major problem throughout the region, it is particularly pressing in impoverished drug transit countries such as Honduras, where criminal elements are easily able to offer enough cash to win the loyalty of underpaid officials. In many countries where police corruption is rife, reform programs often flounder in the face of insufficient political will and underfunding.

A notable pattern identified by the report is the fact that increased police numbers do not equate to a lower homicide rate, with many of the world’s most violent countries maintaining a much higher police to population ratio.

Where a pattern can be seen is in the number of police per homicide investigation, with the most murderous countries having less than 20 officers per case, compared to 500 per case in the least violent countries. Of course, establishing any correlation in these figures is problematic.

Prisons

Prisons

Another factor contributing to the rate of homicides is the prison situation, with the Americas registering astronomically high prisoner numbers compared to other regions — more than four times the “prisoners per 100,000 population” rate and “prisoners convicted of homicide per 100,000 population” rate than the next closest regions (click on UN graph to open in new window).

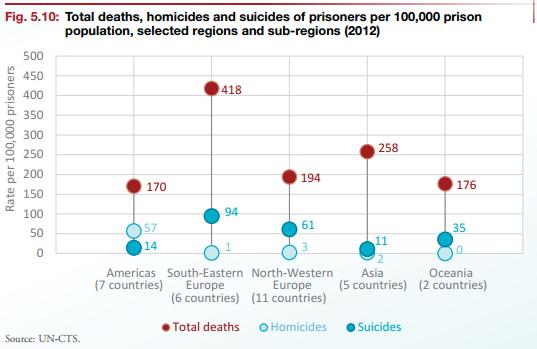

While the incredibly large prisoner population in the United States undoubtedly has an effect on these figures, Latin American prisons suffer chronic overcrowding and endemic violence. This contributes to murders not only in the prisons, but the establishments themselves act as criminal “finishing schools,” which also drives up the homicide rate when jail-hardened criminals leave prison and commit further crime, including killings. According to the report, homicide rates in the region’s prisons are commonly up to four times higher than in the outside world, and there are up to 57 times higher than in other regions’ penitentiaries (click on UN graph to open in new window).

The shocking situation sporadically hits international headlines if a prison explodes into deadly riots — as has been seen in the likes of Venezuela and Brazil. Driving much of the violence are multi-million dollar illicit prison economies, with prisoners running extortion rackets and drug trafficking enterprises out of their jail cells and in many cases acting as the authority within prison walls.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of Prisons

Hopes for Improvement

Yet while the security situation in much of Latin America may be dire, the report offers some cause for optimism based on El Salvador’s gang truce and Brazil’s Police Pacification Units (UPPs). In the case of the gang truce, the report underscores the drop in homicides in the immediate aftermath of its implementation, while it lauds the social initiative built into the UPPs — where authorities in Rio de Janeiro enter violent slums and set up “proximity” policing programs linked to state provided social services.

Though the time between the report’s compilation and release have seen fissures appeared in both the gang truce and the UPP program, there are still positive lessons to be taken from both that could influence similar future schemes in the region — namely the efficacy of placing social inclusion and community development at the heart of violence prevention schemes.

In the case of El Salvador’s crumbling gang truce, there was early optimism over some of the pioneering social programs implemented to integrate gang members into society. However, providing enough jobs for the country’s thousands of gang members was an impossible task to achieve overnight, while public unrest began to bubble over the concentration on homicide prevention — with extortion and other crimes continuing and perhaps even increasing.

For the UPPs, one of the key criticisms leveled has been the failure to follow up on security guarantees and promised social programs. While the UPPs remain popular, spikes in violence have led to complaints that authorities have not kept their word in the aftermath of police actions to enter slums.

In both cases, the prospects of social benefits and inclusivity have brought initial positivism followed by disappointment, pointing to the doomed nature of processes initiated without the political will to see them through.

- Homicides

- security policy

- Prisons

- What Works